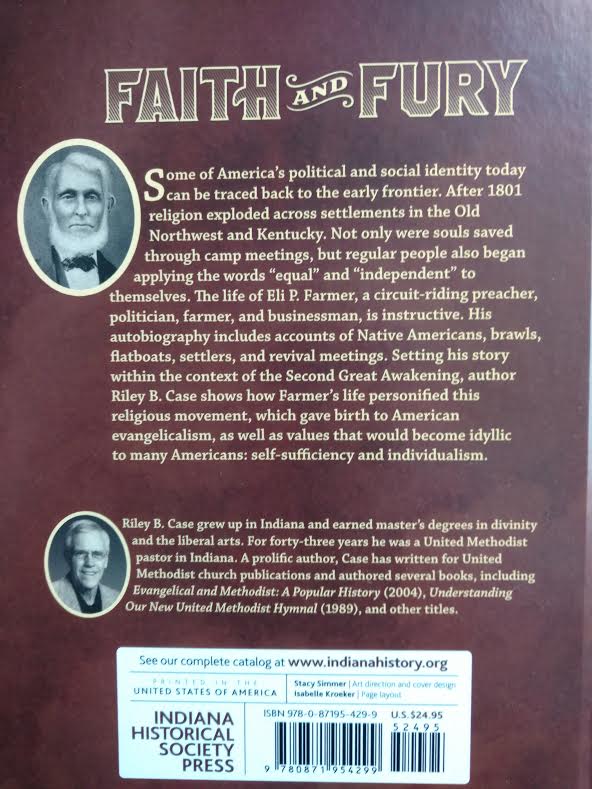

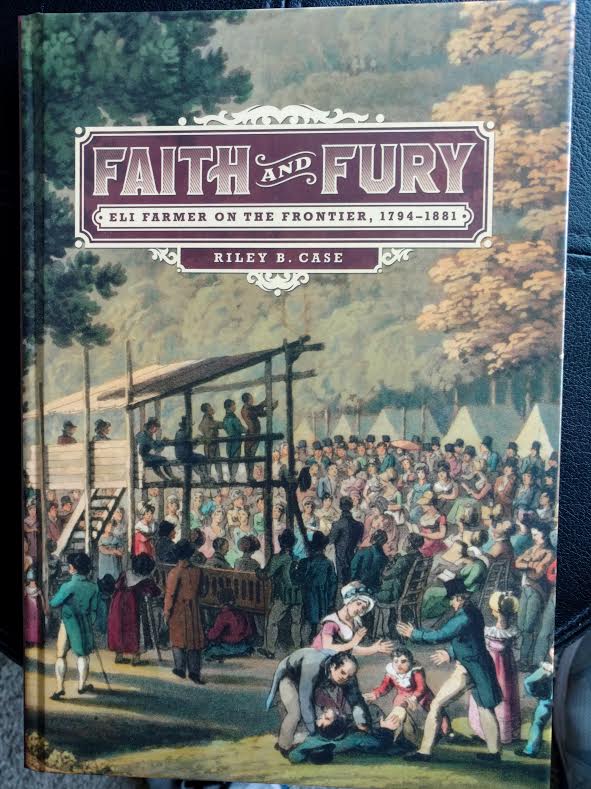

Faith and Fury Eli Farmer on the Frontier

This book

was released on September 19, 2018 by the Indiana Historical Society. The Indiana Historical Society is known for its You Are There live

interactive exhibits and from September, 2018 through Spring 2020 the

exhibit will feature an incident out of the Eli Farmer book that took

place in Danville, Indiana on May 14, 1839. It involves a great

revival in which a Methodist (Eli Farmer) and the Methodists actually

cooperated with Baptists and Presbyterians.

The book is actually Eli Farmer's autobiography and covers his life

through 80 years. Much of that time he was a Methodist circuit rider

who (by his statistics) took 5,000 members into the church. Much of the

book covers the Western Revival, especially the years 1820- 1840.

During that time while the population of Indiana increased by over

3,000% Methodism grew by over 9,000%. Camp meetings were perhaps the

biggest reason for the increase. The book explores how these camp

meetings introduced some practices and emphases that helped redefine the

word "evangelical" in the American context. Some of these include the

introduction of the "altar," camp meeting music, the necessity of

conversion for church membership and a movement toward sectarianism and

individualism in American religion.

Of

course Eli Farmer did other things besides ride the circuit and hold

camp meetings. He got into brawls; he was a state senator; he held his

own evangelistic crusade among the slaves before the Civil War; he was

in the army during he War of 1812; he tried to be in the army during the

Civil War but was (obviously) too old so he became a volunteer

chaplain; he was editor of a rabble-rousing newspaper.

Some

excerpts

On preaching to the Indians: p. 80. "My friends of the

'Creek Nation" were fond of attending church. I could frequently tell

when I entered their territory by the foot-prints leading off in the

direction of the place of worship, the prints being made with

moccasins."

On the religious culture of the

West, p.70: "But in the West, at least in the opening decades of the

nineteenth century, there was no established religious culture and,

therefore, no established standards to determine what constituted

religious extremism. Revivalism did not challenge the prevailing

culture since there was nothing to challenge. Revivalism became part of

and helped to create the religious culture on the frontier. Thus, if

revivalism stressed religious experience, religious experience became

part of the religious culture. If distinctions based on class or wealth

or gender or race were blurred in revivalism, so, too, where they

blurred in the religious culture. If revivalism emphasized the

importance of the individual as opposed to outside authorities and

tradition, so developed a religious culture that lent itself to

sectarianism, or the creation of numerous Christian denominations, each

with specific doctrinal beliefs that separated them from other

denominations or sects..."

On the introduction of the altar and its identification with the "invitation." p. 44: "There

is no precedent for anything like the revivalist's altar at any time or

at any place or for any other group within Christendom before the first

decade of the 1800's. The American camp meeting introduced the use of

the altar; it was not used by the Wesleys in England nor during the

First Great Awakening in the North Atlantic states. It was, in fact,

not used even at Cane Ridge, nor in any of the camp meetings described

before about 1807 to 1810."